Windmill CB0048

The music

The composer writes:

“…from a thatched hut draws upon a particular strand of Chinese culture: the Chinese scholar who withdraws, temporarily or permanently, from society. The thatched hut was the place where the great Tang dynasty poets Du Fu (Tu Fu) and Li Bai (Li Po) withdrew from the world. Their example was followed by many others, including the poet Bai Juyi (Po Chu-I), author of Record of the Thatched Hut on Mount Lu, and Xia Gui, the Song dynasty painter of Twelve Views from a Thatched Hut. The scholarly recluse cultivated poetry, calligraphy, painting, chess, and music—arts in which the hand is directed by the mind, thereby revealing the true character of the individual.…

“There is one short quotation in this quartet (at the start of the fifth movement) from a Chinese musical source. For the rest, the musical language of the quartet owes as much to modern Western music (notably Satie, Webern, and Cage) as it does to Chinese musical traditions. In my search for the musical means to create this quartet, I was influenced by the forms and sentiments of classical Chinese poetry, which attempts to express the inexpressible through words, and by Chinese philosophy, which holds that the extremely diverse and constantly changing appearances of the world are all emanations of a single ordering principle—the Dao (Tao). ‘Looking at the objective world’ and ‘looking within’ are the twin foundations of Chinese art; this closely corresponds to my own approach to music. The seven movements are conceived as a cycle, like seven poems on related themes. There are apparent differences in style between movements, but over the cycle there are parallelisms that emerge between movements and parts of movements.

“My interest in classical Chinese scholarly arts is primarily in the way they express ideas and sentiments that are still relevant today. ‘Though times and happenings alter and differ, may men in what moves them be brought together.’ [Wang Xizhi (303–361), Lantingxu (Orchid Pavilion Preface)]”

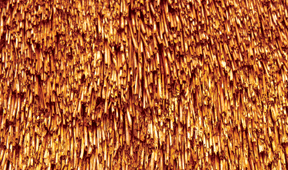

Windmill: “Australia’s indigenous inhabitants survived for 50,000 years on what their ‘country’ had to offer them. When Europeans arrived, human relationship with the land changed. European settlers often displayed ignorance and arrogance, but also stoicism, courage, and a fierce determination to survive in an inhospitable climate. Given the frequency of long periods of drought, farming ventures that began with high hopes often ended in despair. Without a supply of water, agriculture is unsustainable; fortunately, deep beneath much of the continent lie vast, ancient waters. The distinctive steel windmills that dot the Australian outback pump up life-giving water in the often desolate landscape. Many are now rusting away, replaced by solar technology. If you get close enough to one you can hear its distinctive creaking sound, stopping occasionally, resuming as the breeze picks up.”

The composer

Stephen Whittington is an Australian composer and pianist who began performing contemporary music in Adelaide in the 1970s, giving the first Australian performances of music by Christian Wolff, Terry Riley, Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton, James Tenney, Alvin Curran, Terry Jennings, Peter Garland, Alan Hovhaness, George Crumb, Claude Vivier, Morton Feldman, and many other composers. An extended stay in California in 1987, and particularly his meeting with John Cage at CalArts, proved a powerful stimulus to his work. On returning to Australia, Whittington began composing in a new style that combined elements of minimalism, polystylism, and chance procedures.

His keen interest in other art forms has led to his various one-man multimedia shows: The Last Meeting of the Satie Society (2000); Mad Dogs and Surrealists (2003), incorporating music, poetry, and film; and Interior Voice: Music and Rodin (2006). In 2006 he appeared at the Sydney Opera House with Ensemble Offspring for the Sydney International Film Festival, presenting a program of live music for four classic silent movies. In 2007 The Wire magazine listed Whittington’s performance of Morton Feldman’s Triadic Memories as one of “60 Performances that Shook the World” over the last 40 years.

Whittington presented performances at the 2009 Adelaide International Film Festival and the Vienna International Dance Festival 2009 (Austria), and at the Printemps Musical d’Annecy (France) in 2010. His string quartet …from a thatched hut, commissioned by and dedicated to furniture designer Khai Liew, premiered in 2010, the year that also saw the release of the four-CD set Journey to the Surface of the Earth, a collaboration with Domenico di Clario. In 2012, Whittington directed John Cage Day, a 10-hour performance that included his eight-hour performance of ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible) and a Musicircus, incorporating many Cage works, including Concert for Piano and Orchestra. Also in 2012, he traveled to Kyoto, Japan, to study the relationship between Japanese garden design and music. Later that year he appeared as pianist and composer at the Turbulences Sonores festival in Montpellier, France, where his Fallacies of Hope for string quartet and piano was premiered by the Australian String Quartet with the composer at the piano. In 2013, Cold Blue Music released a recording of his Music for Airport Furniture, recorded by Zephyr Quartet. Whittington toured China in 2014, where Windmill was played multiple times, including in concerts at Shanghai Conservatory, Central Conservatory (Beijing), Beijing Foreign Studies University, and Shenyang Conservatory.

His recent works include Fake Gallants (2015) for Baroque ensemble; Autumn Thoughts for piano (2015), which was premiered by the composer at a 2015 recital in Beijing; A la maniere de M.R. for piano trio (2016); and Fragments for P.B. for chamber ensemble and electronics. Whittington’s sound and video installation Hallett Cove—One Million Years (2015), uses continuously evolving video footage and sound controlled by uniquely designed software to explore the area’s geological landscape.

The performers

Zephyr Quartet, which has been described as “creatively adventurous and multi-talented” (The Australian), is a genre-defying string quartet that, since its inception in 1999, has dedicated itself to expanding the boundaries of art music via diverse collaborations, drawing inspiration from and working with artists from the worlds of theater, dance, literature, visual art, environmental art, design, film, and media art.

Zephyr, whose members also compose and improvise, is based in Adelaide, Australia, and regularly performs in festivals across Australia and overseas, enjoying frequent airplay on ABC Radio and TV. The quartet, which maintains an ongoing commitment to the development and promotion of contemporary classical music, often commissioning and performing new works by living composers, has worked with such diverse musicians as Jóhann Jóhannson, Stars of the Lid, JG Thirwell, and Jherek Bischoff. Among the group’s many projects are Hunting: Gathering, a collaboration with designer Khai Liew and composer Stephen Whittington (SALA Festival 2010); Impulse, with Leigh Warren & Dancers (Edinburgh International Arts Festival 2012 and Holland Dance Festival 2009); and MICROmacro, a live visual art and original music performance (Adelaide and Perth Fringe Festivals 2012). Zephyr received the prestigious Ruby Award for Innovation for its 2006 Electro-Acoustic Project, and the 2012 State Award for “Performance of the Year” from the Australian Art Music Awards. Zephyr Quartet has released five CDs of the group’s original music, and in 2013 Cold Blue Music released Zephyr’s recording of Whittington’s Music for Airport Furniture (CB0038).

“These four musicians have collaborated with an extraordinarily wide range of other practicing artists and have significantly expanded listener notions of what the string quartet medium stands for.” —The Adelaide Review

Comments

“Whittington’s extensive resume can seem daunting. Born before ‘Rock Around the Clock,’ the artist has lived through the entire rock era yet has continued to be a champion of the avant-garde, somehow managing to resist the long, slow decline of many artists whose sound is stuck in a particular decade. His interest in multi-media works, including a recent sound and video installation, demonstrate his fascination with the now. While his historical and cultural insights mark him as experienced, in sound, he still seems young.

“The ten-minute Windmill may be a third the length of the other piece, but it receives top billing: the title, the cover photo, and the closing spot. At first, the sounds seem like creaky, un-oiled metal, until one realizes, that’s the point. Australia’s steel windmills are now mostly abandoned, yet continue to turn in the wind. Once upon a time, they marked the boundary between life and death for settlers who themselves endangered the indigenous populace. The turning of the windmill is echoed in the circular, even-tempered pace of the strings. Once in a while, the music stops, as if the breeze has died, picking up again for a moment before stalling again. One begins to think of the windmill as a metaphor for society, for progress and decline, for new starts and deserted technologies. A certain nobility is present in these tattered, rusted beasts, just as it was in the people who erected them. The irony is that the windmills alone, without strings as their voice, continue to exist as multi-media installations, their original purpose discarded.

“…from a thatched hut unfolds in seven movements, and reflects Whittington’s fascination with Chinese poetry, in particular the withdrawal to the thatched hut for solitude and inspiration. This composition allows the Zephyr Quartet to showcase their talents, in particular their self-control and ability to inject a large amount of feeling into a small space. One hears romance in these movements, and philosophy, and tension—a tension that is eventually resolved. Whittington is quick to point out that only a tiny fragment of the piece is distinctly Chinese; the rest is impression and homage. He and the quartet are enormously successful in adopting the timbre of another culture’s music. During the opening moments of ‘Gazing at the moon while drunk,’ one feels the need to look again at the liner notes and to confirm that the composer is in fact Australian.

“Poetry and instrumental expression turn out to be a perfect match, in that each seeks to express something beyond words. Poetry needs precision in order to be effective, a precision imitated here through the careful placement of notes. The ink is in the well; the poems are in the ink. As each movement unfolds, one imagines the poet drawing closer to the divine. ‘Scratch head, appeal to Heaven’ is filled with a desperate longing. The solitude of the thatched hut implies the others from which one has withdrawn; the loneliness of the music implies an Other toward whom the longing is directed. The hut lies between two types of engagement; it’s not as lonely as it seems. As the artist revisits his early themes in the later movements, he injects them with new energy. The cycle is complete, ready to start anew.” —Richard Allen, a closer listen

“Australian composer Stephen Whittington writes that his interest in Chinese philosophy is most apparently manifest in the dichotomy between the objective world and that within. Not really a dichotomy at all—maybe better to call it a continuum—it can be heard in both pieces comprising this second Cold Blue Music release dedicated to his work. Windmill renders the process of multiplicity and unity easiest to hear. Inspired by the creakings and silence of Australia’s windmills, maximal impact is generated from a limited series of pitches, all in higher registers. If this comparatively brief work has what I hesitate to call “Minimalist” repetitional procedures as part of its dialectical motion, its rate of change is ironically quite rapid, encompassing timbre and space. The introduction of what is either a G-sharp or A-flat is both magical and monumental, especially over a G-major sonority. Somehow, the work’s concluding silences conjure shades of Haydn’s joke quartet with added mystical flavor.

“…from a thatched hut raises the stakes. Its subject matter is the reclusive ancient Chinese artists and poets who create introspectively self-revealing works from the thatched huts of their alienation and meditation. While the dynamic world of Windmill is fairly narrow, at least within its own parameters, Thatched Hut opens with a whimper and then a bang as a single tone radiates out into crescendoing microtones. Think of one gesture from the second movement of Shostakovich’s fifteenth string quartet stretched, magnified and amplified, and you’re in the proper orbit. However, vast changes in timbre, articulation and dynamics are unified by the kind of recurrence that brings elements from Nietzschean, Hindu and Chinese philosophy together. Small and large-scale revisitation, both intra and intermovemental, forge and govern the quartet’s circuitous path. While Whittington points out that only the fifth movement contains direct quotations from traditional Chinese music, the whole is informed by it, thriving on slides, pentatonic motives and a certain central stillness, despite constant motion.

“The playing of the Zephyr Quartet is as miraculous as the recording is superb. No strangers to Whittington’s music, the group is immersed in every detail, every hairpin dynamic shift and every overtonal unison. They embody perfectly the unity and diversity so important to Whittington’s compositions. This is one of the finest string quartet discs I’ve heard since the Kronos Quartet waxed Terry Riley’s Salome Dances for Peace, and I cannot recommend it highly enough.” —Marc Medwin, Fanfare magazine

“The seven short movements of …from a thatched hut spring directly from Whittington’s ongoing interest in Chinese history and tradition…. [He] has traveled extensively in China and there is a definite Asian sensibility in several of these pieces— similar to what one hears in the music of Lou Harrison…. In all seven of its movements, …from a thatched hut is an enlightening exploration of the inner surfaces of self-examination, reflection, and introspection….

“Windmill … precisely conjures up the worn and rusty bearings of a remote windmill, spinning purposefully along in the empty landscape. At 3:30 the sounds slow and stop briefly, as if the wind had slackened and then revived. A more leisurely tempo follows, underscoring the age and somewhat decrepit state of the windmill, all perfectly in keeping with the unkempt condition of these machines. As Windmill continues, the stops and starts become more frequent and the silences longer in duration. The tempo slows again and the pitches fall as well, adding to the perception of a machine that is slowly running down in the still landscape. At the last the creaking sounds are very low and infrequent, as the wind finally dies away completely.

“The playing by the Zephyr Quartet here is mesmerizing and completely convincing—Windmill is wonderfully vivid musical image that completely captures its subject.” —Paul Muller, Sequenza21

“The title of the new album is Windmill, which is also the title of the second of two compositions on the CD…. Both pieces may be said to be based on impressions; but only Windmill derives from the visual. The impression of …from a thatched hut is more cultural in nature, dealing with Chinese scholars of the past that lived as hermits (anchorites without any of the Christian connotations).

“The windmills that Whittington had in mind are those constructed in isolated areas in order to bring underground sources of water to the surface. When farming first began to be practiced west of the Mississippi River, just about every individual farm depended on such a windmill. Any number of movies captured the haunting qualities of the creaking sounds made by both the rotating blades and the pumping mechanism.

“Whittington tried to capture those sounds in Windmill; and, allowing him the benefit of artistic license, he did a pretty good job. However, what makes the piece particularly compelling is what might be called its rhetoric of isolation. The suggestion is that, on any given farm, it is often the case that the windmill is the only source of sound; and, once Whittington establishes the nature of that sound, he punctuates it with extended periods of silence. Those silences blur the boundary of when the piece actually ends, an effect that is even spookier when one is listening to a recording than when one is watching the piece being performed.

“The title of …from a thatched hut comes from two of those hermits evoked by the music. The first of these was Bai Juyi, who was a successful politician until a change in the balance of power forced him into exile. Since he was a devoted practitioner of Zen, he saw exile as an opportunity to think on less worldly matters; and he documented his thoughts in the book Record of the Thatched Hut on Mount Lu. Whittington’s other source is the Song dynasty landscape painter Xia Gui, known for painting hand scrolls of prodigious length. One of these was called Twelve Views from a Thatched Hut.

“Those familiar with Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, a book compiled by Paul Reps from a variety of sources of Zen and pre-Zen writing, will probably be familiar with the sorts of hermits that inspired Whittington to compose …from a thatched hut. (Those who do not know the book may still know some of the source material, since John Cage appropriated many of the anecdotes for “marginalia” in several of his books.) In many ways Whittington’s suite makes for excellent music to accompany reading Reps’ book. Indeed, Cage’s own autobiographical statement mentions the Indian singer Gira Sarabhai as one of his sources of inspiration: “The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences.” It is not unreasonable to approach …from a thatched hut through its capacity “to sober and quiet the mind,” resulting in greater susceptibility to the Zen teachings that Reps documented.” —Stephen Smoliar, The Rehearsal Studio

“The music is, to these untrained ears (easily admitted), fairly traditional modern classical music. Introspective but not always ‘quiet.’ There are two pieces here, …from a thatched hut, in seven parts, and Windmill…. That piece, with its minimally changing string work, I liked quite a bit; it reminded me indeed of a windmill.” —Vital Weekly (Netherlands)

“Familiarity with Australian composer Stephen Whittington’s background engenders certain expectations about what awaits on Windmill, his Cold Blue follow-up to 2013’s Music for Airport Furniture and played, like its predecessor, by the Adelaide-based Zephyr Quartet. Also a pianist, Whittington performed works by figures such as Terry Riley, Alvin Curran, George Crumb, and Morton Feldman in the ’70s, but it was a 1987 meeting with John Cage at CalArts that proved pivotal. Upon returning to Australia, Whittington began incorporating elements of minimalism, polystylism, and chance procedures into his composing style. Subsequent to that, works of varying kinds were created, among them 2003’s multimedia show Mad Dogs and Surrealists and live music for classic silent films at the Sydney Opera House three years later. Cage’s impact on him persisted beyond that initial meeting, as intimated by the directing role Whittington assumed for 2012’s John Cage Day, which featured ten hours of performances honouring the provocateur, whereas the recent AV installation Hallett Cove—One Million Years (2015) involved custom-designed software operating on video footage and sound to explore the area’s geological terrain.

“All of which might lead one to expect experimentalism and chance operations to be part of the compositional design of Windmill and …from a thatched hut, the two works presented on the thirty-six-minute recording. Yet while it’s certainly possible that such aspects have been incorporated into the material, the pieces are more conventionally tonal and melodic than anticipated. They’re very different, however: the seven-movement …from a thatched hut draws heavily from Chinese musical traditions, even if the composer declares that its musical language is as much indebted to modern Western composers, specifically Satie, Webern, and Cage; Windmill, on the other hand, is a single-movement ten-minute setting that sonically evokes the hydraulic movements of the structure.

“With respect to …from a thatched hut (whose title alludes to the idea of the Chinese scholar who withdraws from society for purposes of contemplation, study, or otherwise), Whittington identifies one brief quotation at the start of the fifth movement as an explicit reference to a Chinese musical source, but to these ears the tradition’s influence extends further than that, even if subtly. So while there’s no denying the erhu-like character of the strings in the fifth movement, a plaintive quality is evident elsewhere that’s also reminiscent of Chinese folk music. One hears that clearly during the lovely second part, ‘Gazing at the moon while drunk,’ for instance, where the vocal-like cry of glissandos lends the music a mournful character. By comparison, the expressive fourth movement, ‘Scratch head, appeal to Heaven,’ adheres more closely to Western musical tradition, yet its staggered layering of vibrato-heavy string tones is as elegiac in effect. Conceived by its composer as a seven-part cycle that allows for stylistic contrasts and parallelisms between movements, …from a thatched hut is rendered by Zephyr Quartet with the sensitivity of a Chinese brush painting.

“Written with the steel windmills of the Australian outback in mind, Whittington’s delicate title composition evokes the rusting wheeze and creak of the apparatus as it dredges water from beneath the sometimes barren land surface. A breezy sing-song quality asserts itself as the patterns rhythmically see-saw in hypnotic motion, such lightheartedness rather ironic given that solar technology now threatens to render the time-honoured technology obsolete. In presenting two works, the release offers an admittedly small sampling of Whittington’s oeuvre, yet it’s a nevertheless satisfying one that whets the appetite for more.” —Ron Schepper, Textura

“…from a thatched hut was written in 2010. Zephyr plays the seven-movement piece with attention to detail. The piece forms an arc. It begins and ends with the same haunting 440 hz. tutti tremolo. The composer claims the influence of Cage, Webern, and Satie, but I’m basically hearing Satie. His essay on Satie’s Vexations for me almost describes this piece: ‘Vexations,’ he writes (and I would say this also applies to his own work …from a thatched hut), ‘lingers in the memory as a vague impression, the details effaced as soon as heard…static, undramatic…reinforced by repetition…a sound object…a two dimensional surface.’

“Graham Strahle describes Whittington’s Windmill (1990) as ‘classic…musical minimalism.’… I can say that G major flat ninth set up throughout the 10-minute one-movement work in tutti harmonics is beautifully realized and delicately bowed.” —Andrew Violette, New Music Connoisseur

“A really beautiful discovery is the music of Australian composer Stephen Whittington that is featured on this Cold Blue CD of two compositions for string quartet, performed with great sensibility by the Zephyr Quartet. In the first piece, …from a thatched hut (in seven movements), long chordal passages sketch vast natural scenes, which become animated when modal-flavored melodies suddenly appear, then mysteriously disappear. In Windmill, insistent and irregular repetitions of a single terse phrase suggest the uncertain journey of a traveler, lost in desolate lands. The constructive use of silence, the reference to Asian culture, the relationship to visual arts, and the poetic ambience, recall composers like Peter Garland, Peter Sculthorpe, and Kevin Volans, with whom Whittington shares the search for arcane beauty, pure, but at the same time aware of the turmoil of our time.” — Filippo Focosi, Kathodik (Italy)

“It is easy to get lost in Stephen Whittington’s minimalist music. His unhurried works on this release are hypnotic, drawing in the listener with short repetitive shards of material and longer phrases that continuously circle back on themselves. From a thatched hutcaptures the intensely introspective atmosphere of the scholarly recluse of Chinese culture. The texture is sometimes silky, sometimes brittle, but always delicate. V, ‘Journey of an Immortal,’ is the best movement, with melodic phrases spontaneously flowing in and out of the foreground. My favorite piece is Windmill, inspired by steel windmills of the Australian outback. The music seems to exist on two different planes of listening: while the music eerily resembles the actual sound of creaking metal in the wind, there is no attempt to disguise the string timbre. The listener is left acutely aware of both the apparent reality and the illusion. It is an entrancing piece, one that I find myself revisiting again and again.” —American Record Guide